I’ve tried to write about the New York City Marathon many times. Each year, its magic somehow surprises me, catches me off guard, and, without fail, makes me cry. Admittedly, the crying part is not so surprising. I’m a crier, welling up the moment emotions—any emotions—get heightened. Still, the marathon is different.

In the past—2018, 2022, 2023—I’ve tried to write about the race the day after running it myself. This has never worked well. Usually, the next day, I’m in a strange state that approximates a hangover—a triumphant hangover—which is not a particularly clear-headed place to write from. This year, though, I spectated. So, I reflect:

In a 2011 TED Talk, Brené Brown spoke on the power of vulnerability. She asserted that the most important thing in our lives—the thing that gives our lives meaning—is connection.

“By the time you're a social worker for ten years, what you realize is that connection is why we're here. It's what gives purpose and meaning to our lives,” Brown said.

In the running world, there has been a lot of chatter about “community.” I think connection can often get conflated with community. I want to clarify that I am not saying that the New York City Marathon is a day of community. Community feels like it’s been overused at this point—churned through the machine of capitalism, of enormous run clubs, appropriated as a marketing ploy by brands to sell products. I’m wary of the term.

Connection, however, is different. It’s what we often seek out in community, what we experience on the day of the marathon.

I kept thinking about Brown’s TED Talk as I watched the runners this year. What struck me, standing behind the barricades, shouting strangers’ names as they ran past, is that in New York, the marathon is a day of collective vulnerability.

Brown talks about how connection is only possible with vulnerability: “In order for connection to happen, we have to allow ourselves to be seen… And I know that vulnerability is the core of shame and fear and our struggle for worthiness, but it appears that it’s also the birthplace of joy, of creativity, of belonging, of love.”

It’s vulnerable to run a marathon—to dedicate hundreds of hours training for something, something that will hurt, something that is hard, something that could go awry at any point, even on race day. Furthermore, it’s vulnerable to strive toward this massive accomplishment in front of thousands of strangers. That is brave.

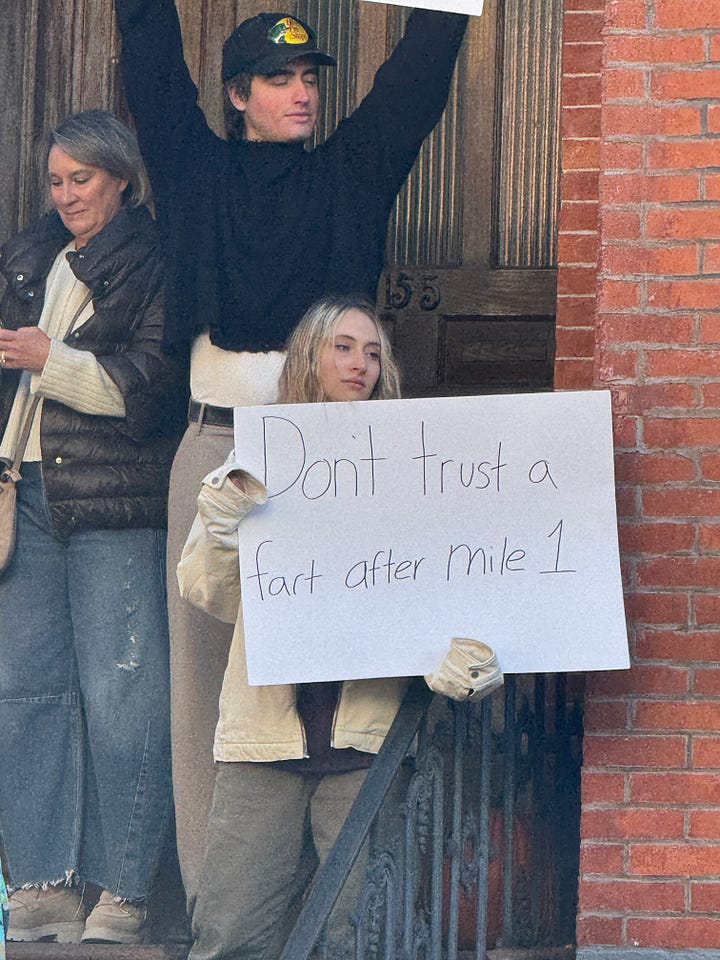

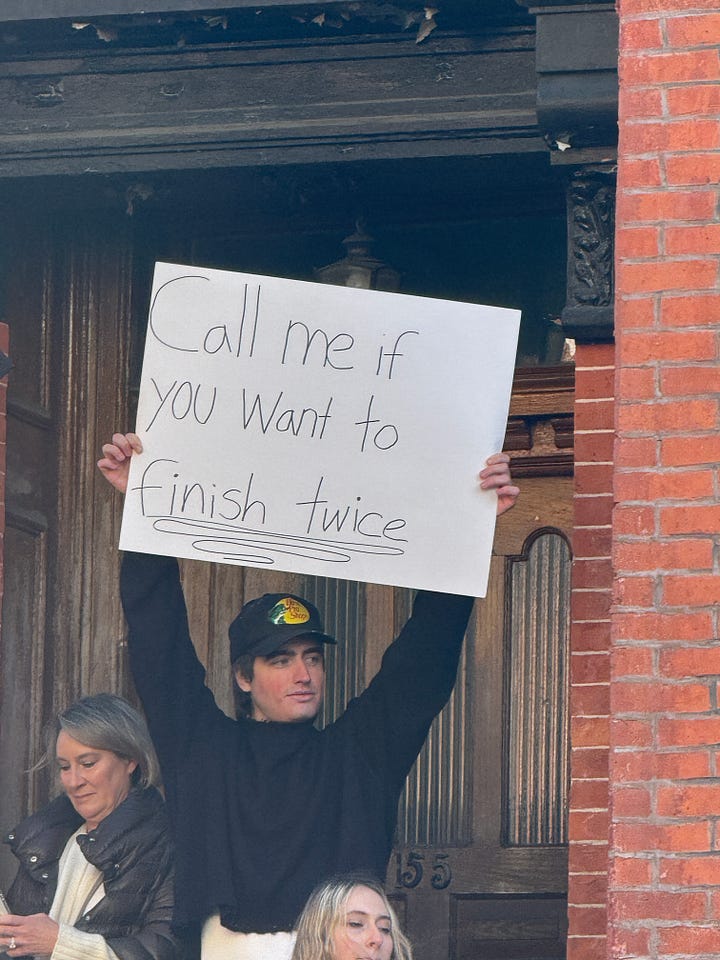

But it’s also vulnerable to show up to the race and cheer, to make signs for people you don’t know, to yell out strangers’ names printed on their bibs or written in electrical tape on their shirts. It is vulnerable to make your voice loud enough for them to hear you, for everyone around you to hear you.

The New York City Marathon reminds us how powerful connection can feel, and it shows us that connection can only happen when we let ourselves be vulnerable.

As Brown says, the biggest obstacle to vulnerability is shame, which she defines as “fear of disconnection.” But at the New York City Marathon, there isn’t any room for shame—no space for fear—because connection is happening all around us. The energy between runners and spectators is enduring—the hugs between runners and their friends and family, the giant face cutouts, the live bands and DJs, the booming music, the cowbells, and hilarious signs. The possibility for disconnection is completely eradicated.

In her research, Brown found that there’s something that highly connected people have in common: “They didn’t talk about vulnerability being comfortable, nor did they really talk about it being excruciating as I had heard earlier in the shame interviewing. They just talked about it being necessary. They talked about the willingness to do something where there are no guarantees.”

I think this is what everyone who comes to the marathon, whether to run or to watch, understands at some level: that vulnerability isn’t easy, but it’s necessary. It’s hard to run 26.2 miles. It’s hard (maybe not quite as hard) to scream encouragement for hours on the sidelines. But we all understand, implicitly, that it’s worth it.

I feel grateful to be part of the connection around the marathon: to have led one of the many shakeout runs in the city leading up to race day (thank you, Fruit Gang, for showing up to my Halloween run). To be a part of the innovation that is happening in running technology. To be one of the first to wear On’s LightSpray shoes. To listen to panels comprised of brilliant women talking about the ways running makes individuals and communities resilient.

Thank you to everyone who chose to be vulnerable yesterday. The magic, as always, was undeniable.